Indonesia’s Batam Dropping Its Economic Luster

It has long been seen as the bright new frontier for Singapore companies determined for space to broaden but Batam’s economic promise appears to be fading, battered by forces from within and without.

Its ace cards – low cost land, low-cost labor, proximity to home base – still resonate with Singapore firms though without the force of a few years ago.

Its ace cards – low cost land, low-cost labor, proximity to home base – still resonate with Singapore firms though without the force of a few years ago.

The rise of other industrial enclaves, whether or not in Johor or China or fast-rising states like Vietnam, have dented Batam’s appeal but it’s problems nearer to home that fear businesses more.

“Indonesia should be its natural market but Batam is strictly an export zone and there’s a firewall between them. It’s a flawed protectionist strategy.”

A person known solely as Mr Tan, a manager at a Singaporean-owned shipyard in Tanjung Uncang, on the western side of Indonesia’s Batam Island, shifts uncomfortably in his seat, smiling evasively, when the topic comes up.

No surprise, it is Batam’s most sensitive subject – the perpetual demand of its raucous and spirited labor drive for larger wages. When prodded, Tan, admits: “If there is no more wage benefit to stay here, investors could move out.”

Labor unrest could properly develop into the island’s Achilles heel, notes Robert Broadfoot, managing director of Hong Kong-based Political and Economic Risk Consultancy.

He notes that the regulatory atmosphere is tilted in favor of labor, which encourages a confrontational scenario between labor and management.

Strikes in Batam are becoming an annual affair. “Most of the time, the calls for are affordable and the strikes last a day,” says a supervisor at a firm in Batam.

However late last yr., the protest involving thousands of workers from 200 companies turned ugly and lasted three days.

“While they look like isolated incidents and do not detract BBK (Batam, Bintan and Karimun) from its fundamentals, they remind us to be sensitive in managing the native workforce,” says Lee Yee Fung, Commerce Company IE Singapore’s regional director based in Jakarta.

The mission to turn Batam, a as soon as sleepy fishing outpost with just 6,000 residents, into a hive of business and tourism activity remains intact regardless of the ructions on the commercial front.

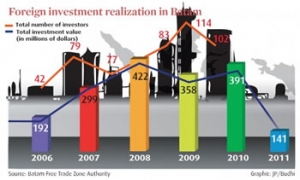

The inhabitants is now more than one million, there’s a workforce of about 300,000 and one million guests come yearly, drawn by six “worldwide standard” golf courses 25 industrial parks, 50 hotels & resorts and two marinas. Between 2003 and 2010, apart from 2009, its economy grew over 7 per cent each year.

More than 1,200 overseas corporations function there, drawn significantly by the proximity to Singapore.

But the place – and the mission itself – wants a turbo-charged jolt.

That got here partly two weeks in the past when Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono renewed the pledge to drive development in Batam, Bintan and Karimun, which make up one in all two free commerce zones in Indonesia.

Singapore’s role is crucial given its strategic place in the “development triangle” between Malaysia’s thriving Johor area and the three Riau Islands.

For hundreds of thousands of Indonesians who have found jobs on Batam, the largest island in the Riau Archipelago, Singapore has turn out to be a lifeline.

“Batam exists because of Singapore,” says a local, born in Jakarta and one of about 300,000 who came to the island for work.

In virtually all of Batam’s development benchmarks, Singapore sits on the perch. It is the island’s largest investor, having contributed $933 million (S$1.2 billion) or 70 per cent of its foreign direct funding over the first half of last year. Half of Batam’s exports head to Singapore.

It is mostly firms from the precision engineering, electrical elements and electronics manufacturing and marine and offshore supporting industries which have set up shop on Batam, says Lee Yee Fung.

The advantages are aplenty.

“Land is cheap; infrastructure is cheap, labor abundant. We save 20 per cent in overall enterprise value,” says K. T. Ang, managing director of ASL Marine Holdings, a Singapore-listed delivery agency with a shipyard in Batam which employs 3,000 contract employees, mostly Indonesians.

Huge firms aren’t the only ones flocking to the area.

A lady recognized only as Ms Lo bought an oceanfront villa on a 328ha island between Singapore and Batam, which is the third favored vacationer spot in Indonesia, after Bali and Jakarta.

She is considered one of a huge band of hopefuls who have scooped up real property in Batam and neighboring islands banking on their sheer promise.

But that promise, that potential, doesn’t look as shiny as it did just a few years ago.

Rivals like China’s southern metropolis of Shenzhen, also as soon as a small fishing village that grew to become a particular financial zone about the same time as Batam, has thrived.

Malaysia has poured billions of ringgit into Iskandar Malaysia in south Johor since 2006, additionally to leverage its proximity to Singapore.

While Shenzhen is an export processing zone, a lot of its merchandise is additionally offered in China.

However Batam, constructed on the concept of an export-oriented industrial space, isn’t meant to compete with different industrial areas in Indonesia, which market their merchandise throughout the country.

“Indonesia should be its pure market but Batam is strictly an export zone and there’s a firewall between them. It is a flawed protectionist technique,” Broadfoot says.

One other weak hyperlink is connectivity.

“As close as Batam is to Singapore, it is still a ferry ride away. It’s simpler for factories in Singapore to maneuver to Johor,” says Broadfoot, referring to the two direct street links between Johor and Singapore.

About 70,000 Singapore passport holders cross the Causeway to Johor a day, considerably more than some 62,000 Singaporeans who visited Batam in January.

There was discuss of constructing a tunnel or other land link from Singapore to Batam however the prices in addition to the safety and political dilemmas make that more pie-in-the-sky than viable policy.

“Batam won’t ever be close to its potential till it makes these elementary changes,” Broadfoot says.